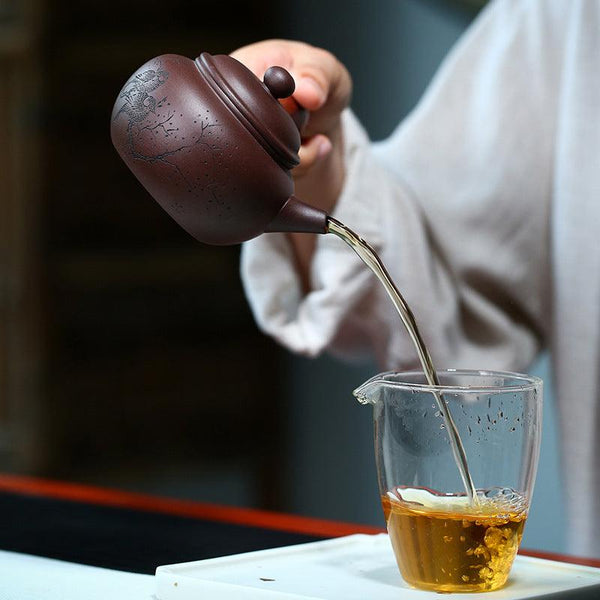

The artistic status of the purple clay teapot goes beyond mere functionality, embodying a unique fusion of material science, craftsmanship, cultural philosophy, and aesthetic evolution. This fusion has earned purple clay a high status in global ceramic art and intangible cultural heritage. As the culture spreads, purple clay teapots are sold worldwide.

Top 5 Traditional Masters: Creating Classics with Ancient Tech

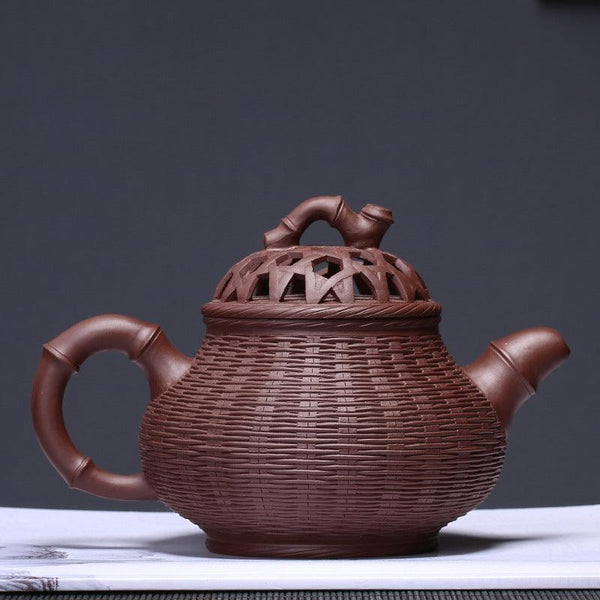

Traditional craftsmen adhere to manual techniques and emphasize the unity of "form, spirit, energy, and posture". These works often combine practicality with literary aesthetics.

Gu Jingzhou (Master of Teapot Art: 1915-1996)

- Representative works: Xuehua Teapot (replica), Suhui Teapot

- Design concept: Pursue the unity of "shape, spirit, spirit, and state", emphasize simple and dignified lines, and rigorous and precise craftsmanship. Gu Jingzhou advocates "teapots for daily use", taking into account both practicality and artistic beauty.

Xu Hantang (Master of all-shaped vessels: 1932-)

- Representative works: Hantang basin series, antique pots

- Design concept: Focus on the comprehensiveness of traditional techniques, the works are simple and smooth in shape, and the techniques are clean and neat. He is good at integrating multiple styles such as flower vases and light vessels into sand basin design, taking into account practicality and collection value.

Zhou Guizhen (Chinese Arts and Crafts Master: 1943-)

- Representative works: Mansheng handle, Jiyu pot

- Design concept: By integrating the strengths of Wang Yinchun and Gu Jingzhou, the works are characterized by their rigorous structure and warm temperament. Emphasizing the "tight fit" craftsmanship precision, reflecting the oriental implicit aesthetics.

He Daohong (Chinese Ceramic Art Master: 1943-)

- Representative works: Ningli pot, Dingxin pot

- Design concept: The original "He style" is based on the core of a thick and powerful feeling. Focus on the fullness and thickness of the pot body, the elastic lines, and convey the philosophy of "power is contained within".

Gu Shaopei (Chinese Arts and Crafts Master: 1945-)

- Representative works: High-spirited pot, Longevity bottle

- Design concept: advocating "serving life", the design should be adapted to the nature of tea (such as Pu'er needs a wide-bellied pot). Good at making large vessels, integrating bronze and jade carving elements, and highlighting national characteristics.

Four Key Points for Authenticity Identification

1. Clay

Authentic purple clay exhibits a natural particle distribution, as well as good water permeability and air permeability. Imitations are mostly uniform and dull, and often have a glaring "thief light" after firing.

The most precious clay is the Qing Dynasty Tianqing clay, which presents a rare color known as "blue in blue" and is rare in the world due to the depletion of the ore veins. Shao Daheng's Tianqing clay ball pot is a typical representative, which was sold for ¥322,000 in the 2025 China Guardian Spring Auction.

Modern imitations are mostly colored with chemical materials, lacking the "sand eyes" (iron precipitation spots of the original ore) and warm patina of natural ore sand.

2. Craftsmanship traces

The craftsmanship of purple clay pots is divided into two types: full hand-beating and mold forming. The former is expensive and can be identified by the irregular "mud door folds" on the inner wall. Secondly, the seams of handmade pots are more natural.

The hand-molded "fat mud connection marks" can be seen in the pots of the mid-Qing Dynasty. At the same time, modern high-end imitations often utilize 3D scanning to reproduce, but they lack the "micro-deformation" agility of handmade pieces.

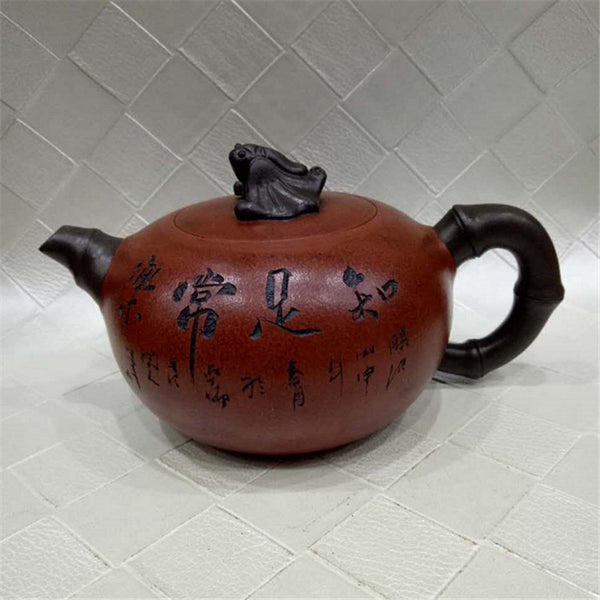

3. Charm

Authentic products have a consistent charm (such as the mechanical balance of the spout/handle), while imitations are often exquisite in parts but out of balance overall.

Gu Jingzhou's pots are famous for their unity of "form, spirit and state", such as the line and surface transitions of the Tibi pot, which are like calligraphy strokes. He Daohong's Ningli pot's "accumulated tension" requires decades of practice.

4. Seal inscriptions

In 1948, Gu Jingzhou changed "Jingzhou" to "Jingzhou", and his works from the same period were stamped with the "Yihai Yizhou" seal. In 1961, during a special period, he reused the "Shouping" seal from his early years. Such historical clues are the core basis for dating.

Common problems with imitation seals: soft seal text (the original work is neatly engraved), gaudy seal color (the old pot has deep and transparent seal), and time dislocation (such as using a 1980s seal to cover a "Qing Dynasty pot")